Anthroprosaic

2007, a series of small bronze sculptures and a model of a high-rise building

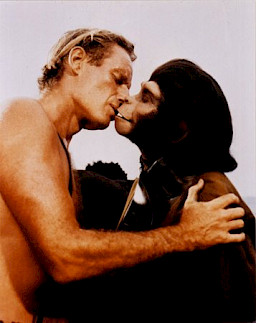

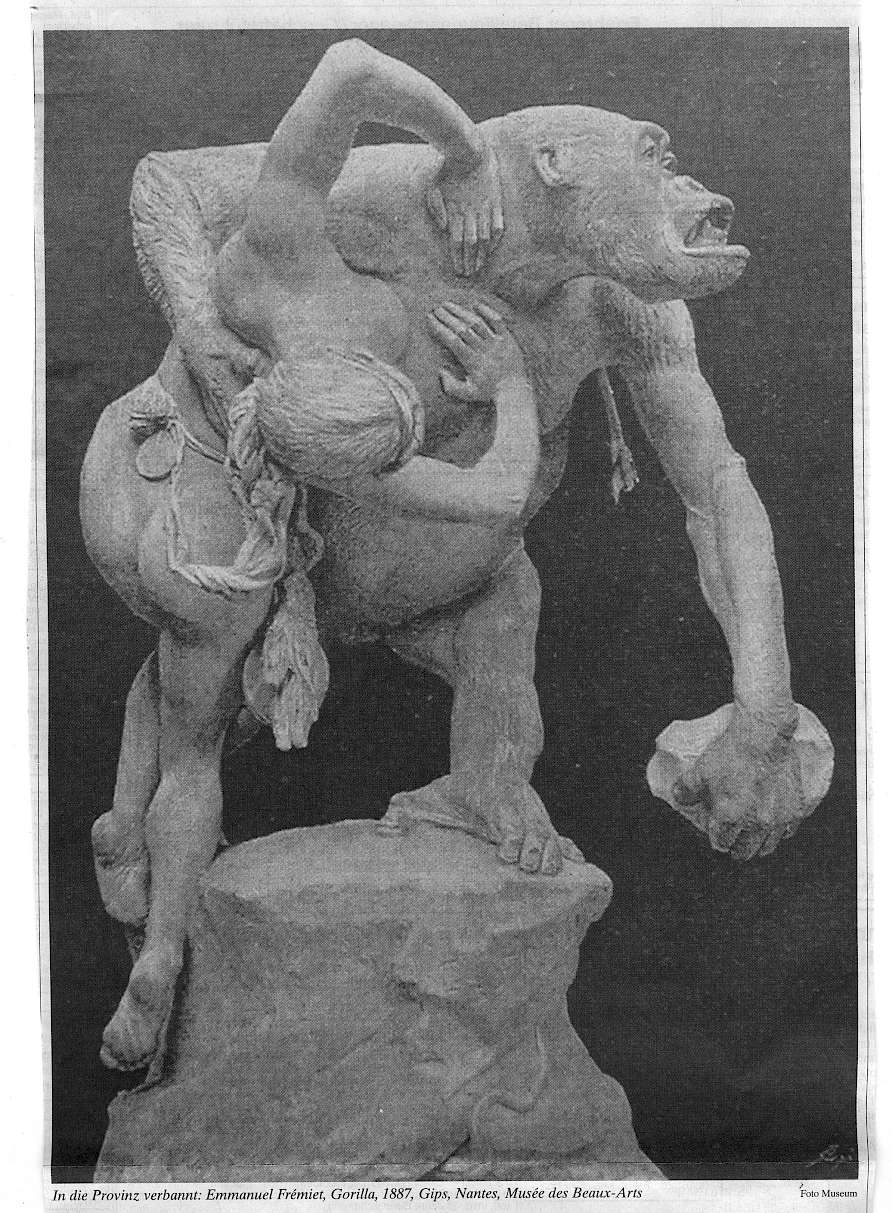

An an abandoned human environment, a troop of ape-like beings interact with the mundane remnants of our human society. Anthroprosaic poses the philosophical question of the distinction between humans and animals on critical activities: sex, violence, language, tool-use, image production, self-awareness and reflective thinking.

As summed up by Italian philosopher Emanuela Cenami Spada: Anthropomorphism is a risk we must run, because we must refer to our own human experience in order to formulate questions about animal experience. The only available “cure” is the continuous critique of our working definitions in order to provide more adequate answers to our questions, and to that embarrassing problem that animials present to us.

The “embarrassing problem” hinted at is, of course, that we see ourselves as distinct from other animals yet cannot deny the abundant similarities. There are basically two solutions to this problem. One is to downplay the similarities, saying that they are superficial or present only in our imagination. The second solution is to assume that similarities, expecially among related species, are profound, reflecting a shared evolutionary past. According to the first position, anthropomorphism is to be avoided at all costs, whereas the second position sees anthropomorphism as a logical starting point when it comes to animals as close to us as apes.

(Frans de Waal, The Ape and the Sushi Master, 2001)

A group of apes may be referred to as a troop or a shrewdness of apes.

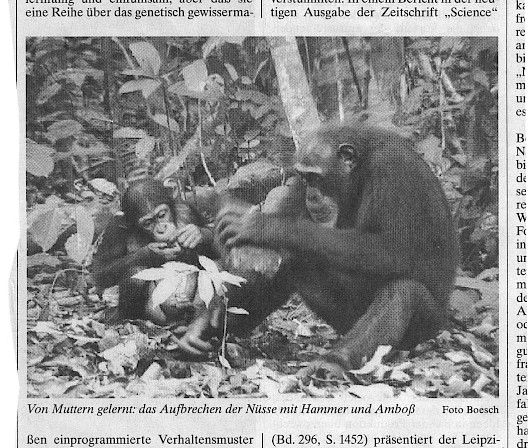

It is a big difference to see x, or to see x as y; and the main theme of cognitive psychology is the ability to understand something as an entity—the stone as a tool or weapon or stool, and not just as a lump.

The hand of the chimpanzee is quasi-human, the hand of Jackson Pollock is almost animal. (Salvador Dali)

Gary Winogrand: Basically, I mean, ah – well, let’s say that for me anyway when a photograph is interesing, it’s interesting because of the kind of photographic problem it states – which has to do with the … contest between content and form. And, you know, in terms of content, you can make a problem for yourself, I mean, make the contest difficult, let’s say, with certain subject matter, that is inherently dramatic. An injury could be, a dwarf can be, a monkey – if you run into a monkey in some idiot context, automatically you’ve got a very real problem taking place in the photograph. I mean, how do you beat it? (“Monkeys Make the Problem More Difficult: A Collective Interview with Garry Winogrand,” ASX, 20 Jan 2012)

|

|

|

|

|

The Infinite Monkey Theorem is a statement in probability mathematics, stating that an infinite number of monkeys, typing randomly on an infinite number of typewriters will eventually come up with the complete works of Shakespeare - or the Bible, or the perfect library containing all books written by human writers through the whole history. Following Jorge Louis Borges’s “The Library of Babel”, this library would contain everything: the minutely detailed history of the future, the archangels’ autobiographies, the faithful catalogues of the Library, thousands and thousands of false catalogues, the demonstration of the fallacy of those catalogues, the demonstration of the fallacy of the true catalogue, the Gnostic gospel of Basilides, the commentary on that gospel, the commentary on the commentary on that gospel, the true story of your death, the translation of every book in all languages, the interpolations of every book in all books.

The Monkey Shakespeare Simulator was a website randomly generating letters and comparing the results with Shakespeare’s complete works. The record in 2007 was 24 letters from “Henry IV part 2” after 2,737,850 million billion billion billion simulated monkey-years “RUMOUR. Open your ears; 9r”5j5&?OWTY Z0d “B-nEoF.vjSqj[...” matched “RUMOUR. Open your ears; for which of you will stop The vent of hearing when loud Rumour speaks?...”